“A lamp may be as much an object of art as a painting or a piece of statuary. In fact, it should be.” — Tiffany Studios, a company advertisement

A piece of text included in Tiffany Studios New York promotional materials, we now know that the genius behind bringing this powerful statement to life and to verity belonged not only to the nominal Louis Comfort Tiffany, but to a group of innovative, self-empowered, and superbly talented women: the self-styled “Tiffany Girls.” The accomplishments of these women, who are now known and celebrated for designing countless of Tiffany Studio New York’s most aesthetically beautiful, technically complex, and financially successful lamps and objects of art, went largely unrecognized until nearly a century after the closure of their famous workshop in Corona, Queens, New York. Comprised of thirty-five female artists, designers, and artisans, at the height of its scale and productivity, the Women’s Glass Cutting Department at Tiffany Studios was helmed by a woman whose prodigious talent was matched only by her relentless drive and dedication to the cause of establishing a place for women in the innovative arts.

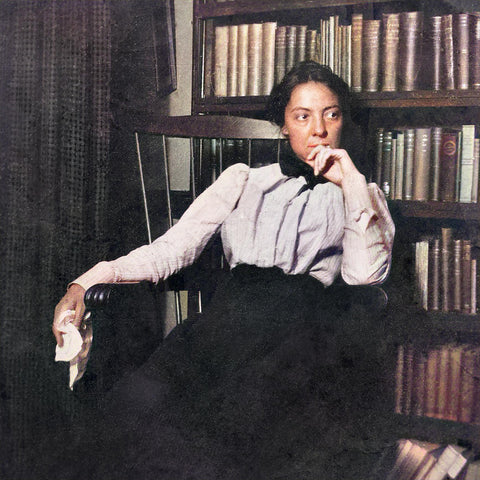

Clara Driscoll—born Clara Wolcott in Tallmadge, Ohio in 1861—came to Tiffany Studios New York after an impressive educational background at the Cleveland Institute of Art and then the Metropolitan Museum of Art School in New York City. Driscoll’s academic focus was what was then known as “Architectural Decoration,” a largely male-dominated field of study that would come to inform Driscoll’s very particular approach to conveying natural forms. Following a strike by Tiffany Studios’ unionized male workforce (the Lead Glaziers and Glass Cutter’s Union) Louis Comfort Tiffany ordered the hire of a small team of female designers to maintain production in his experimental glass factories, a group that included the young Clara Driscoll.

Though it has long been said that Louis Comfort Tiffany was inspired to create the Tiffany leaded glass shade by Thomas Edison’s invention of the incandescent light bulb—or, indeed, at the suggestion of Edison himself—that canonized wisdom is now being challenged by Tiffany scholars, as it is now thought that Clara Driscoll first suggested that Tiffany begin his foray into leaded shades. So keen was her eye, and so deft were her abilities, in all aspects of creating leaded glass lamps and mosaic objects (including bookkeeping and administration, in addition to design creation and production oversight) that within five years at the firm she had thirty-five female employees reporting directly to her.

Despite Louis Comfort Tiffany’s dependence on the Women’s Division, the women of Tiffany’s workshop were not allowed to continue their work were they to become engaged or married, and so Clara Driscoll was forced to leave her position twice, the first in 1889 when she married Francis Driscoll—who died unexpectedly in 1892—and again in 1896 when she once again became engaged, returning to the firm the same year after her fiance mysteriously disappeared. It was after this second return to Tiffany Studios New York that Driscoll’s department of women accomplished what became a truly prodigious output, and she herself was able to generate some of Tiffany’s most famous and sought-after designs. The celebrated Dragonfly, Poppy, and famous Wisteria lamp (which, in its day was sold for an incredible price of $250) are all now recognized as the brainchildren of Driscoll.

In fact, it is now entirely known and acknowledged that Driscoll was responsible for the introduction of the famous floral designs in Tiffany shades. Tiffany not only allowed the Tiffany Girls and Driscoll herself to pursue the creation of these designs, but he also maintained that the conception of naturalistic motifs stay within the Women’s Glass Cutting Department, as he believed women to be not only more dexterous, but, more importantly, to be far more sensitive to color, shade, form, and the artistic dispersion of light than their male counterparts. Driscoll involved herself purposefully in not only the design, but also the full assemblage of each of her shades, choosing particular pieces of glass to be included or discarded from the process in order to recreate the beauty of the natural form that inspired her—a monumental task, considering her beloved Wisteria alone has over 2,000 pieces of individually chosen glass forms. Despite not being publicly acknowledged, it is well-recorded within the firm, and proudly reported by Driscoll herself in letters to friends and family, that the Tiffany Girls produced more windows, lamp shades, and mosaics in less time—and with fewer mistakes—than their male counterparts. Louis Comfort Tiffany himself inspected the Women’s Glass Cutting Division every Monday morning, and he was rarely disappointed.

At a salary of $10,000 a year, Clara Driscoll still did not make as much as less skilled and experienced male members of the Tiffany workforce, but she could be considered one of the highest paid women in New York City. Unlike her male counterparts, Driscoll and her team were not allowed to unionize, and so were constantly tasked with proving their worth to the company, a task complicated by the efforts of the all male Lead Glaziers and Glass Cutter’s Union, who objected strongly to Louis Comfort Tiffany’s hiring of women, and to Driscoll’s prominent position in particular, even leading a strike in 1903 in an effort to eliminate the Women’s Division entirely. In the negotiations following the strike, the male Glass Cutter’s Union succeeded in limiting the number of women Driscoll was allowed to lead in her division, although she did win the exclusive rights to design and engineer many major lampshades, as well as the very limited and exclusive luxury items, like mosaic boxes, jar, and jardinieres that so excite Tiffany Studios collectors today.

Irrespective of her accomplishments and accolades, Clara Driscoll’s name was only publicly acknowledged by Tiffany Studios once in her career, when she was named as the winner of the Bronze medal for the design of the dragonfly lamp at the 1900 World’s Fair in Paris. Along with other important Tiffany Studios employees, such as chemist Aurthur Nash, her name was scrubbed by Louis Comfort Tiffany from public recognition, as he preferred, and worked diligently to ensure that his name alone was branded on all of Tiffany Studio’s pieces, particularly the most significant of them. Indeed, Driscoll’s name was lost in the history of Tiffany Studios for close to a century before two talented scholars serendipitously discovered two independent troves of letters, one housed at the Queens Historical Society and the other at the Kent University Library, written by Driscoll to family and friends describing in astonishing detail the several years she spent at Tiffany Studios. The late scholar and respected independent curator, Nina Gray, and professor Emeritus of Art History at Rutgers University, Martin Eidelberg, discovered within weeks of each other not only the existence of Driscoll and her legacy, but also of each other’s work and uncovering of the subject. Along with Margaret Hofer, the Curator of Decorative Arts at the New York Historical Society, the two Tiffany experts worked to bring the story of Clara Driscoll and her compatriots to light in the exhibit “A New Light on Tiffany: Clara Driscoll + The Tiffany Girls,” which brought Clara Driscoll’s name and accomplishments to the forefront of the academic conversation on Tiffany Studio’s history.

And what would Louis Comfort Tiffany have said of this incredible rewriting of history? “I think he would have died,” answers Eidelberg, noting that although Tiffany awarded Clara Driscoll and her team of women a remarkable opportunity at the time, he also quashed all recognition of her achievements, and left her and her female counterpoints in a position to continuously fight for their place within his organization. In a 1904 interview, Driscoll is quoted as acknowledging this fight, saying, “This is indeed rather difficult work, but when one has a passion for a certain brand of industry, she does not pause when a difficulty must be overcome […] The work is a new departure for women”—a departure she championed valiantly, and with great success.

Here at Macklowe Gallery, we wish to continue the fight to rewrite the historical narratives that are so well-established and so easily held onto, those that have dismissed the tremendous accomplishments of great female talents and leaders within male dominated fields, in eras of even more severe male domination. We aim to present in the most frank and accurate manner possible the true history of Tiffany Studios New York. Our ongoing project and ultimate goal is to continue to shed a light on the great men and women who engineered the beauty that is its legacy.