A movement that eschewed historicism, romanticism, and so called “academic art,” Art Nouveau largely abandoned the established artistic practices that preceded it, including the eons old custom of landscape painting. Fluidity of line, asymmetry, near abstraction, and a bold synthesis of structure and decoration dominated compositions at the turn of the 20th century, supplanting traditional desire to create a window into another dimension. In place of traditional landscapes, Art Nouveau adopted a fastidious attention to natural details in a manner inspired by Japanese woodblock prints, very newly available in Europe at the time. The whiplash arc of a dragonfly’s wing or the diaphanous shimmer of a peacock’s feather were granted the attention previously reserved for seascapes and mountain scenes; while backgrounds became flat and abstracted, emerging as ethereal framing devices rather than deep sets of value mimicking a horizon line.

Though largely forgoing the pictorial rituals that preceded them, the Art Nouveau masters did, occasionally, make careful nods to historical traditions of depicting the world around them. These instances, few in number and sophisticated in nature, speak to a refined understanding of the landscape painting practice, as well as an appreciation of those artistic schools that directly predated or existed concurrently with the Art Nouveau movement. Impressionism, Realism, Romanticism and the Hudson River School had each developed their own placeable approach to the landscape, each approach being revolutionary at the time of its introduction. While Art Nouveau never developed its own approach to the landscape, it did, in these special instances, adopt and honor the landscape practices established by the aforementioned schools of art.

At the turn of the century the very purpose of many traditional modes of artistry were made obsolete by the advent of photography. After the introduction of the camera, artists were no longer charged with capturing the likeness of their surroundings, but instead tasked with an interpretation of beauty that transcended literal translation. Rebelling against the academy, artists at the time argued through visual mediums that their work should transcend the reality of the world rather than transcribe it, a job that now seemingly fell into the photographer’s hands. Thus new artistic practices, such as Art Nouveau, and, notably, Impressionism, emerged. Impressionism, though a stark and disruptive departure from all previous modes of depiction, did still turn its eye toward the landscape, portraying familiar scenes with sketchy, brushy strokes that revolutionized artistic convention. Impressionist painters sought out just that; the impression of a scene, the magic of a glance, the elevated understanding of the eye when it first catches notice of an intimately known vista. With such goals in mind the masterpiece that is Claude Monet’s Impression, Sunrise, among the most famous of all landscape paintings, was born.

Claude Monet. Impression, Sunrise (1872). Oil on canvas. 18.8×24.8". Musée Marmottan Monet, Paris

The painting would come to define the movement that is the celebrated school of Impressionism, and inspire artistic makers worldwide in their departure from established modes of visual representation. Though concurrent movements, Art Nouveau and Impressionism shared few visual touchpoints, with the exception of their shared distaste for academy-established pictorial customs. One important, rare and notable tribute to the Impressionist aesthetic made by an Art Nouveau master is this exceptional work from Daum Nancy. In both Impression, Sunrise and this petite but powerful work, a hazy, airy, near ethereal seascape is grounded in sharp, vertical, optical anchors of distant architecture. The composition of the gossamer lamp shares with an impressionist work an emphasis on light, color and a particular approach to depth that is both delicate and unfixed, but concrete in its effect, as well as a startling similar subject matter and arrangement of visual elements.

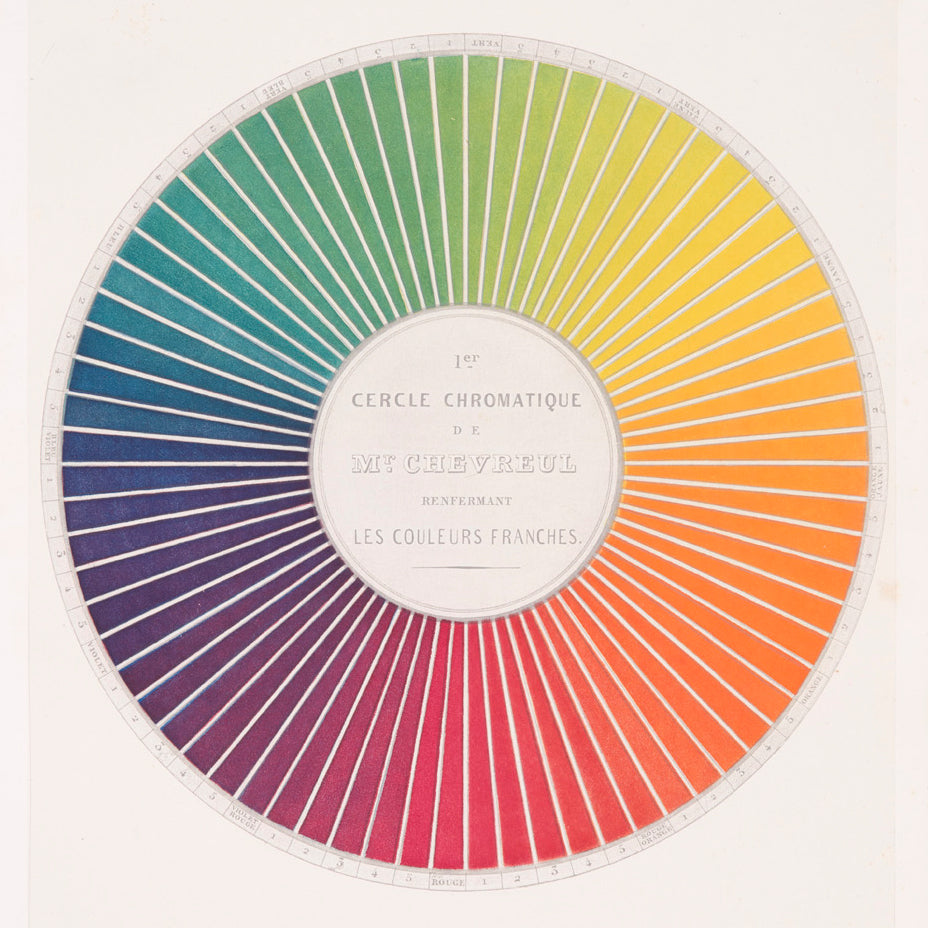

Alongside photography, the development of color theory, a key discovery concerning light, sight and perception, greatly informed the impressionist understanding of visual discernment. Grouping colors into primary, secondary and tertiary tiers, color theory established the “color wheel” as we know it today, and importantly introduced the concept of complementary colors. Many of the Impressionist masters, including Monet, were enthralled with the new theories concerning color, and leaned heavily into the concept of complementary colors to excite. So, too, did Daum Nancy in this composition, creating an arresting feast for the eye in only complementary hues of vibrant orange and satiny green.

Monet and other great Impressionists were taken with natural forms just as the Art Nouveau masters were, particularly adopting the practice of painting en plein air or painting directly out of doors. Such practices were also employed by the French school of Realism, as it was developed by celebrated painters Jean-Basptiste-Camille Corot, Eugene Boudin, Gustave Courbet and, notably, Jean-Francois Millet. The Realist movement achieved peak form and acknowledgement during the period from 1840-1900, solidly predating both Art Nouveau and Impressionism. Like the aforementioned artistic schools, Realism rejected the academic art of its time, favoring, instead, the democratization of art by depicting then modern subjects drawn from everyday lives of the working class, in a true to form natural landscape.

Jean-François Millet. Gleaners (1857). Oil on Canvas. 433×326". Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Jean-François Millet. Gleaners (1857). Oil on Canvas. 433×326". Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Jean-François Millet was among the leading proponents of the movement, and one its most celebrated champions. He created the masterpiece known as The Gleaners in 1857, the piece depicting three women in the midst of gleaning, or scraping for leftover harvest, in traditional garb of the lower class in the Barbizon region of France. In this composition Millet shows the women, of a class and type that would never have been awarded such artistic attention before this age, in monumental proportions and with sculptural attention that recalls the work of Michelangelo or Nicholas Poussin. Executed in a scale that was traditionally reserved for royalty or religious figures, the painting dignifies the plight of the rural poor while highlighting the inequity of their situation by means of a refined but perfectly rendered situational landscape. A perfect representation of the Barbizon horizon, this piece uses the vast and overpowering expanse of sky to symbolize the unattainable reaches and crushing weight of the upper class wealth in France. Meanwhile, the grand expanses of harvest behind the female forms serves as a reminder of the great abundance that is made unavailable to so many worthy souls. The piece thus employs the sensitively rendered landscape to give voice to these faceless but celebrated figures. The work was so important as to inspire Edouard Manet to paint the The Roadmenders Rue de Berne, Edgar Degas to compose Women Ironing, Vincent Van Gogh to create The Potato Eaters and Cezanne to draw up Man Smoking a Pipe (After Millet).

(From Left to Right) Edouard Manet, The Roadmenders, Rue de Berne (1878); Edgar Degas, Women Ironing, (1884-6); Vincent Van Gogh, The Potato Eaters, (1885); Paul Cezanne, Man Smoking a Pipe, (1902)

(From Left to Right) Edouard Manet, The Roadmenders, Rue de Berne (1878); Edgar Degas, Women Ironing, (1884-6); Vincent Van Gogh, The Potato Eaters, (1885); Paul Cezanne, Man Smoking a Pipe, (1902)

And, quite probably, served as the impetus for Emile Gallé to create this magnificent centerpiece. Grandiose in scale and luxe in its great details, this important server is in actuality an homage, a celebration and a sensitive salute to the plight of the rural poor, and particularly to the women of agrarian regions. The upper panel of the server features a lush agrarian setting in which can be found several working figures, unusually un-idealized and un-romanticized, but instead treated with the same gravity and quiet reverence as Millet’s gleaners. In fact, Gallé’s composition similarly depicts the inequities of harvest, with a few men reaping great bounty, while a number of women and children glean nearby outskirts of the field. Just as in the Millet work, the landscape in Gallé’s speaks heavily to the nature of the work, with vast expanses dominating the picture plane in gentle, ominous, and rewarding capacities in turn.

Left: Thomas Cole. View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (1836). Oil on Canvas. 51.5 x 76". Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Right: Emile Gallé, Chrysanthemum Lady’s Writing Desk (1890). French walnut, Fruitwood marquetry. 55.5 x 29.5 x 22.25". Macklowe Gallery

Left: Thomas Cole. View from Mount Holyoke, Northampton, Massachusetts, after a Thunderstorm—The Oxbow (1836). Oil on Canvas. 51.5 x 76". Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City. Right: Emile Gallé, Chrysanthemum Lady’s Writing Desk (1890). French walnut, Fruitwood marquetry. 55.5 x 29.5 x 22.25". Macklowe Gallery

Though rare, this is not the only instance in which Gallé turned to the landscape to express natural beauty. In this other, notable example, we find the master of marquetry quoting not the Frenchman, Millet, but an American, Thomas Cole. Cole, one of the few American painters of his time to gain acclaim across the ocean in Europe, created a formalistic genre of landscape painting within the Romantic movement that became iconic in its day and beyond. The self taught painter, an engineer by trade, created celebrated depictions of the American West, following a process of amalgamating en plein air sketches to create what would become to Cole and his followers the height of landscape painting. Perhaps formulaic at times, Cole’s renowned approach to the landscape is well noted, and often quoted. However, only an artistic eye of equal sensitivity and a mind of equal ingenuity could properly capture Cole’s paired grandiosity of scale and dedication to the minute. An easy comparison can be drawn between Gallé’s elaborate writing desk and Cole’s work, with a large, native tree, or, in Gallé’s case, an ombelle, dominating the left hand side of the composition, a stoic body of water tapering in width as it moves towards the right hand side of the work, and gothic architecture framing the entirety of the piece in both the majority of Cole’s oeuvre and in this very special piece by the Art Nouveau master.

Left: Alphonse Mucha, Pair of "Dawn and Dusk" Lithographs (1899). Handmade paper, Japanese silk pongee matte, Giltwood and gesso frame. 29.75 x 46.5" Macklowe Gallery. Right: Francisco Goya, La maja desnuda (1797-1800), La maja vestida (1800-1805), Oil on Canvas. 38 x 75". Museo del Prado, Madrid

Even the maverick Alphonse Mucha, considered by some to be the forefather of the Art Nouveau movement, and a noted purist when it came to the aesthetic, did, in one extraordinary instance, pay his respects through visual means to a master of another artistic school. In Mucha’s pendant pair, titled Dusk and Dawn respectively, we see overt, but elegant reference made to Francisco Goya’s Romantic masterpieces, The Clothed Maja and its once hidden sister work, The Nude Maja. Referred to as the last of the Old Masters and the first of the modern, Francisco Goya was the famed portrait artist and champion of socially minded Romanticism in Spain from 1786 until his death in 1828. In Goya’s pendant pair, the female form, in one instance clothed and in one nude, presses boldly against the confines of her frame, pushing outward in her slightly exaggerated scale. She lounges brazenly, dominating the unusually horizontal composition with a bold but refined grace, engaging her viewer with steady gaze that revolutionized female portraiture.

Édouard Manet, Olympia. Oil on Canvas. 51 x 74.8" Musée d'Orsay, Paris

Édouard Manet, Olympia. Oil on Canvas. 51 x 74.8" Musée d'Orsay, Paris

The work inspired such comparable masterpieces as Manet’s Olympia, and this important pair of outstanding prints by Mucha. However, in Mucha’s works, the female form, which similarly appears nude and covered in her respective likenesses, is captured lounging in front of elaborate natural backdrops, rather than indoors, as Goya depicts his maja. In Dawn, Dusk , the female forms are just as dominant in the picture plane as a Goya’s, but instead of entrancing the viewer with her gaze, Mucha’s lounging figure instead corresponds her expression to the specifics of her environs. As the sun rises, the lone figure gazes energetically outward over a romantically rendered landscape in blush tones, and, as it sets, closes her eyes against a dramatic natural horizon aflame with reddish hues. While Goya’s Majas clearly focus on the relationship between the subject and the viewer, in Mucha’s quotation it is the central figure’s relationship with nature that takes center stage, and, thus, the landscape unusually becomes the center of the composition.